I was impatient to see Friedrich at the Met, which should have tipped me off that I would be let down. The disappointment had less to do with any curatorial shortcomings than with having too deep a fondness for the painter. It was naïve of me to think that a definitive survey of Friedrich’s work could be mounted outside of Germany. To be fair, the show is didactically rich and installed for ease of comprehension. Though many of my favourites didn’t cross the ocean—and the list of lost pictures is harrowingly long—several key works are included. Still, iconophilia tinged with nostalgia can overwhelm the best curatorial efforts. Friedrich belongs to the handful of artists who formed my aesthetic personality.

A few of the people I’ve been closest to, starting with my father when I was a child, have complained that I live in my head rather than in the world. I don’t believe that’s the same thing as being self-centred, so I never accepted it as a fault. Please forgive the psychological exhibitionism, but it is pertinent to a discussion of Friedrich, the painter of interiority. To be clear, Friedrich did not give me permission to live in my head, the cause of which may be unknowable. Rather, he reassures me that the condition is not unusual and was once thought admirable.

About my head, there’s a vast art gallery in there with an idiosyncratic floorplan. Friedrich’s rooms on the piano nobile have multiplied over the decades since I was introduced to his work in a college seminar on Romantic landscape painting. As I recall, the professor spoke of Friedrich with the same reverence he reserved for Turner, whom he called “perhaps the greatest painter.” That was a bridge too far for me, but I followed him closely on Friedrich. He referred to him as “an iconographer of Protestantism.” Having been raised Catholic, hearing that made me curious about the rival faith to which I had never given a thought.

Correction. When I was a child in parochial school, the teacher told us that heaven would be closed to Protestants. My neighbourhood friends were variously Anglican, Dutch Reform, Lutheran, or United, as well as Catholic. We were a tight gang, so the nun’s remark distressed me. I asked my father to explain. A believer and somewhat religious, he was also a liberal and assured me that the teacher was confused. He said: “Don’t worry about that, boy. All good people will go to heaven, regardless of their religion.”

Consoled, I didn’t think about Protestantism again until I heard the professor’s comment on Friedrich’s Abbey in the Oakwood, a German national treasure that, unsurprisingly, isn’t in the exhibition. It shows the last fenestrated wall of a ruined gothic abbey in a derelict graveyard at twilight. The fragments of institutional faith appear to be returning to nature beneath the angry gnarls of ancient wintering oaks. After reflecting on what might be Protestant about such a picture, I concluded that I needed more information.

If the ardent faith of my childhood had been long abandoned by the time I got to university, Friedrich’s Lutheran-inflected iconography caused me to delve into Christian reform. I carried the curiosity over to another class when I wrote a term paper for Modern European History about the biographical parallels between Luther and Lenin, the revolutionaries bookending the period covered by the survey. Because I felt clever for having unearthed the similarity, when the teaching assistant assigned to my paper gave it a garish “C,” I was incensed. He wrote something dismissive about my comparison being historical nonsense, that I was taking advantage of some “paucity” or other, a word that I had to look up. I should have had the presence of mind to ask if he had ever heard of the GDR, a communist country founded by cultural Lutherans, but I had yet to learn about that. Happily, an appeal to the kinder professor bore fruit. To my ego’s relief, he upgraded me to a more palatable B, explaining that my argument was indeed anachronistic (in 1980) as consensus in the field put communism closer to Catholicism and Protestantism to capitalism—but he had found the paper lively and even thought-provoking. So there.

Back in the Romantic Landscape seminar, the discussion had moved on, but I couldn’t shake my fascination with Friedrich. Accounting for it was a struggle because his pictures weren’t my thing. I loved abstraction, adored Piet Mondrian and found minimalism exciting. In fact, I remember exchanging doodles of Jack Bush’s geometric formats with the fellow aesthete who sat next to me in the seminar—we would sigh inaudibly with every trade. In those days, boldness, clarity, and exhuberance were what I found beautiful in pictures—Friedrich’s gothic gloom evoked adolescent melancholia. Ugh to that. It’s useful to know that the artist’s childhood had been more tragic than I care to get into, and that he was hard-up for most of his life. But there is more to him than sadness. The eye-rolling moodiness notwithstanding, studying Friedrich planted the seed of my eventual aversion to ‘taste’ in art: it interferes with understanding.

While thinking about Abbey in the Oakwood, and especially its conventional pendant Monk by the Sea—a personal icon that I loved seeing in New York, but where its soulfulness looks alien—the intellectual and metaphysical dimensions of visual art were made manifest to me. That’s when I realised that art is so much more than skill and style. Friedrich helped me to understand that aesthetics is only part of the equation. Ideas, positions, arguments, tenets, and traditions, are the raisons d’être of iconography. And nothing expresses a Weltanschauung—a perspective on the world—more succinctly than an eloquent picture.

His faith aside, Friedrich is definitely an iconographer of German Romanticism. Living in Dresden though, he had scant acquaintance with the philosophers of his cohort as they lived elsewhere. We don’t know what he read, but we do know that his pictures weren’t to Goethe’s taste for being too melancholic and reactionary. He painted subjectivity, however, a crucial theme for Goethe, as well as for the thinkers of Jena. According to Andrea Wulf, these were the “inventors of the self,” or what Fichte called “das Ich.”

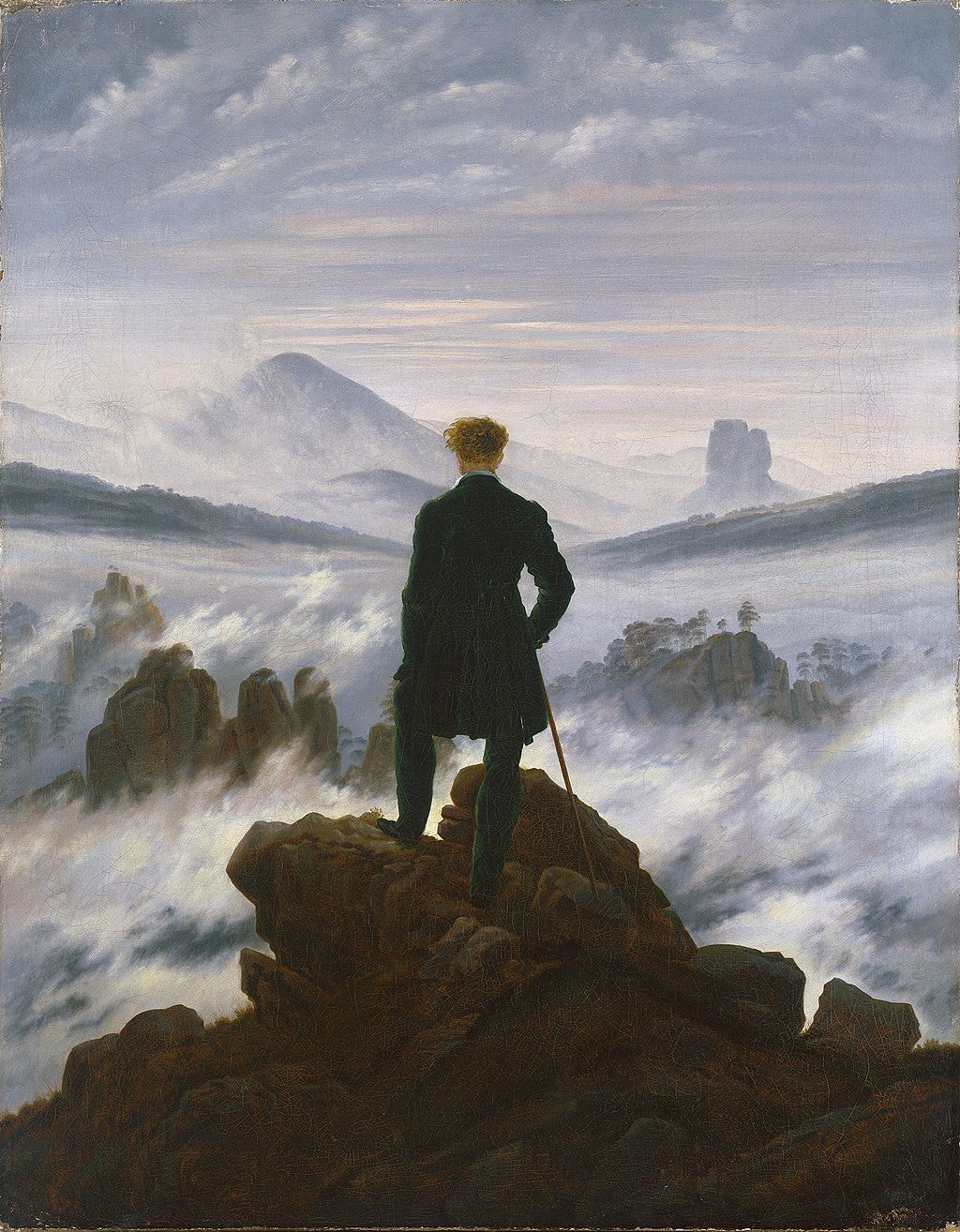

Not everyone agrees, but it has been often speculated that Friedrich’s heroic Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1818, is a self-portrait. If so, it’s the apotheosis of the Christian artist’s introspective Ich. It can also depict, if you like, the spiritually ambitious subject escaping the mists of unknowing.

Incongruously, Wanderer has become the cliché cover of books by Friedrich Nietzsche, a climber of mountains, yes, but a strident anti-Romantic and no friend of the spiritually inclined. With characteristic snark, Nietzsche said of the German Idealists of Jena: “They muddy the waters to make them seem deep.” Pairing Nietzsche with Friedrich isn’t the first marketing decision to swamp an artist’s or a writer’s intent.

Be that as it may, from the distance of two centuries, and despite his Lutheran bona fides, Friedrich strikes me more plausibly as an iconographer of Romanticism than of Protestantism, which famously didn’t want one. Mind you, judging from the silence of his intellectual contemporaries, German Romanticism didn’t want one either. In any case, according to Isaiah Berlin, there wasn’t much difference between Romantics and Protestants east of the Rhine.

Though its proliferation in the corpus makes it seem vanguard, Friedrich’s signature Rückenfigur—the subject seen from behind—isn’t purely original: Giotto used the device, as did Raphael, Dürer (partially), Vermeer, and others who came before him. But Friedrich is the one most identified with anonymous subjects showing their backs to the viewer—more than a compositional device, he gave it meaning. We might go further and say that his trope turns the viewer into a proxy of the painted figure, although convention prefers the reverse. Following my scheme, I become a second order of subject who, like the picture-facing maker himself, stands in the painted figure’s wake. By implication, Friedrich and I are reduced to craning for a glimpse of the ineffable, forever hanging back from revelation.

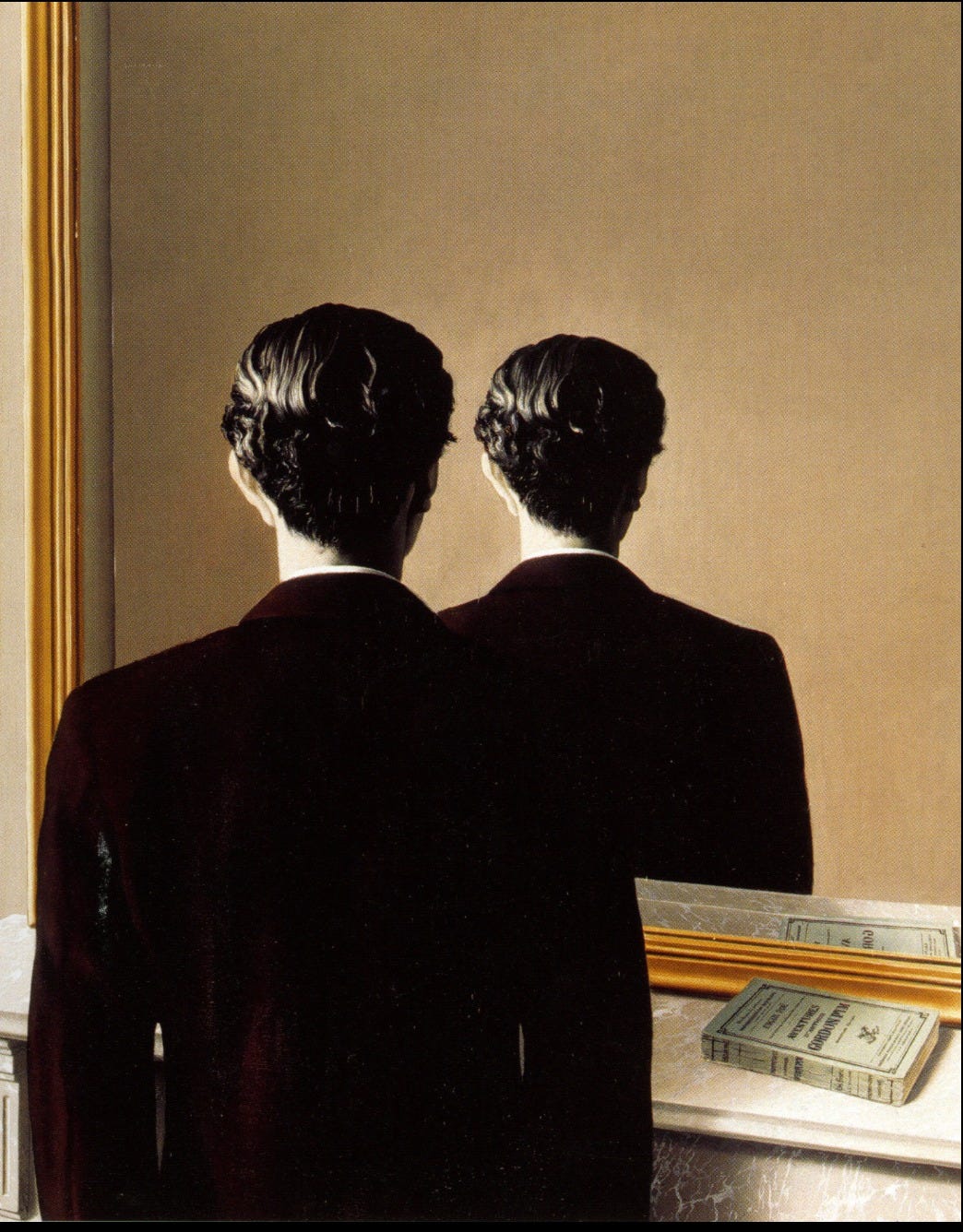

Though probably inadvertent, Magritte’s La Reproduction interdite, 1937, satirises the Rückenfigur and its implications for the viewer. For me, Magritte’s polysemic title—Not to be Reproduced in English—pokes fun at the individuality of the discrete Ich. Notice the copy of Edgar Allan Poe’s gothic novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket on the mantel, in Baudelaire’s French translation. It’s another amusing qualification of Friedrich’s signature subject.

Joking aside, the Wanderer poses on a natural plinth above a mountainous landscape that we look past him to see. It takes no effort to imagine his exhilaration at the majesty of a scene that might exhilarate us too, if vicariously. For me, the subject of the work is neither the figure, nor the scene, but perception and its emotional consequences. We need not see the man’s facial expression to feel his thrill. Even if it won’t instil empathy in every viewer, and even if we have no idea whether his eyes are open or shut, we can easily believe that he’s filled with awe, and I feel him feeling.

Yes, Friedrich’s preference for depicting people from behind was convenient for a committed painter who may have lacked a talent for physiognomy. He was no Dürer in that regard, from the meagre evidence. Turner’s corpus shares a similar paucity of portraits that hints at the same weakness. Does this say something about Romanticism? Even its finer portraitists, Delacroix for example, were more bent on recording psychological states than likeness. That was a job better suited to Neoclassical flatterers. Friedrich’s seductive power as a craftsman lies less in resemblance than in the touching grace with which he depicts texture and light. And of course there’s no point in holding inaptitude for painting faces against a figurative artist. If modernism taught us anything it’s that surpassing skill as a painter or sculptor will not make you significant in art. Ideas are the thing.

Friedrich was fundamental to my Bildung as the artist who liberated me from the prison of taste, but also as the painter who demonstrated that the inexpressible can be pictured. That’s why Robert Rosenblum appends Mark Rothko to his lineage. If you look at Friedrich through the lens of Schelling, his almost exact contemporary, he should have been acknowledged as an exemplar of the idea that “the work of art is the organon of philosophy,” its instrument of knowledge. In Schelling’s hierarchy of intellection, art (writ large) is held above philosophy for its ability to reconcile opposites. I would agree with him, were it still 1818, by saying, moreover, that you can see perception in a picture by Friedrich, a capacity of sentience that cannot be easily described in words, if at all.

My favourite subject in Friedrich is not his Rückenfigur—which, parenthetically, I enjoy more in groups. Intuiting the shared emotion of two or several people perceiving infinity is more interesting to me who, oddly, feels even more included in the scene. Samuel Beckett might have agreed. In his German Diaries, he revealed that seeing a version of Two Men Contemplating the Moon in 1937 on a brief stop in Dresden was the genesis of Waiting for Godot. These days, though, I’m more partial to the trees.

A few years after reunification, I was visiting Berlin’s Alte Nationalgalerie when I came upon a room dedicated to Friedrich’s trees. The dark walls of the broad gallery, and especially the solemnity of my fellow visitors, made me feel as if I had entered the sanctum sanctorum of the Germans. Unlike my intuition regarding Friedrich’s Wanderer, I couldn’t fathom what being in that room must have felt like to the descendants of Hermann. Two thousand years ago, he and his brethren defeated three Roman legions in the woods.

This artist is at his most uncanny, his most spiritual when drawing and painting trees. Nina Amstutz tells us that these were informed by the field sketches of plants by Alexander von Humboldt, et al. But Friedrich’s trees have nothing of the botanical illustration about them. Not only are they portraits, they are portraits of palpably sentient creatures untainted by anthropomorphism. I have no idea how he pulls it off, but Friedrich manages to convince me that trees have souls. That’s paradoxical given that I don’t believe in souls. He clearly did, and like the ruined church and graveyard he shows returning to nature, his Christian spirituality eventually returned him to animism, humanity’s inaugural faith. Honestly, since visiting that gallery in Berlin all those years ago, I see trees very differently from how I did before, and have come to require not only their proximity, but maybe even their fellowship.

It’s unlikely that Friedrich would have agreed with me about the souls of trees. He attempted to represent them as expressions of his own soul. The religious son of a dour Pietist, he would surely have recoiled at the charge of heathen animism. Helpfully, the exhibition’s curators quote him on what he was actually after:

The artist's task is not the faithful representation of air, water, rocks, and trees, but rather his soul, his sensations should be reflected in them. The task of a work of art is to recognize the spirit of nature and, with one's whole heart and intention, to saturate oneself with it and absorb it and give it back again in the form of a picture.

I won’t quibble with a dead man, and certainly not one who so magnificently achieved what he set out to. My point is that his pictures of trees overcome his cultural specificity and the historical anecdote of their creation. I have nothing in common with Friedrich, not ethnicity, history, or temperament. And yet I see what he hoped that I would.

Friedrich’s magic also animates shrubs. Bushes in the Snow, 1827-28, might be the picture that I looked at the longest in the Met exhibition. I don’t fully understand why. Perhaps it was the peculiar quality of the light and its eerie, unheimlich familiarity. Come to think of it, the memory of William Faulkner’s Benjy was unexpectedly aroused. An intellectually disabled man tangled up in the shrubs, his fractured interior monologue opens The Sound and the Fury. Reading it was challenging and transformative for me, on the order of Monk by the Sea and Abbey in the Oakwood, which I encountered at about the same time. More vividly, seeing the picture recalled my own revelation regarding bushes as a nature-loving child in Northern Ontario. One day, alone in the scrub beside the neighbourhood bog, I tugged mightily on a budding willow in an effort to take it home, roots and all. Imagine my astonishment when I discovered, just under the surface of the dirt, that all those twigs formed a single thing.

Honestly, I learn so much from your Ekphrasis! And I will think of this as my daughter and I visit the Met next week.

A brilliant article.