Abstraktes Bild (Abstract Painting), oil on canvas, 120 x 120 cm, 2017.

Abstraktes Bild (Abstract Painting), oil on canvas, 200 x 200 cm, 2016

The Richter show on at Zwirner 20th Street has the city buzzing; the gallery is thick with people as you would expect for the post-war Picasso. Not only is the exhibition pretty wonderful, word on the street says it will be the artist’s last in New York in his lifetime. COVID cheated us of his big survey at the Met in 2019. Cruelly, it was up for a measly nine days.

Richter is 91, but nothing in this exhibition—of paintings, drawings, prints and a big glass sculpture—looks like the work of an old man taking a bow. He stopped painting in 2017, so the show does include the last works in that medium, specifically in the smeary scrapings for which he’s best known. These are some of the most satisfying pictures he ever made, denser, more exuberantly colourful, unmuddied. Yet, the scraping goes deeper in places, more physical, and gets right down to the gesso here and there to reveal the tooth of the canvas. As the last paintings of an artist who relied so much on chance, they are surprisingly controlled. Having perfected the process, they feel far more like the last in a logical sequence than the last of his energy. It may be ‘all he wrote’ but there’s no evidence here that he couldn’t write more.

How magical it would be to see a big Richter museum show of only abstract paintings, a strictly chronological study of a single typology in the straight-faced painter’s corpus, without the self-interruptions of the larger practice. We could watch how he resuscitated gestural abstraction in the 1970s through an updated chroma and stealthy pastiche. We would see how he set us up, like frogs in a slowly warming pan, to witness the obliteration of the deliberate human hand. Richter’s heroic, full-body self-erasures have more dire implications for civilisation, and feel likelier to me, than Pollock’s atomic dance of death. But this show is thrilling and even optimistic, as if he were calling his own bluff about the apocalypse.

8.11.21, 2021, pencil on paper

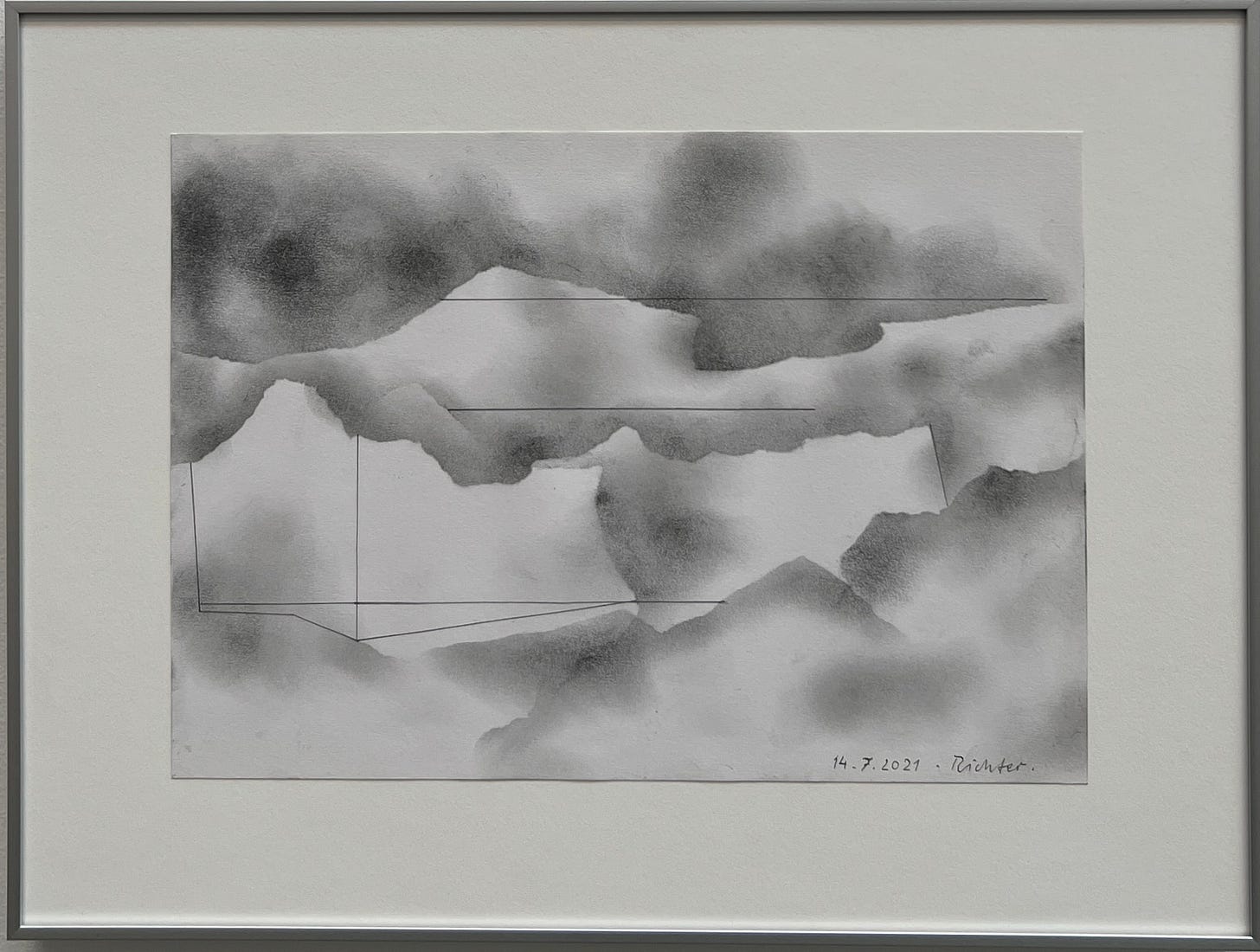

14.7.21, 2021, pencil on paper

After decades of pleasure, it only dawned on me in this show that pastiche is Richter’s default mode. Let’s treat that word carefully; his special brand of pastiche is not parody. If he is a humorist, Richter is infinitesimally subtle, so not prone to jokes. His pastiche has no specific object and yet it feels familiar and as inevitable as something by Mozart. If you said that Richter contributes to the modernist canon by filling in blanks, I wouldn’t agree with you. To me, he rearticulates major themes of modernism to improve and refresh them for a single corpus. He reprised photo-based figuration, from jarring photorealism to greeting card sfumato; he brought his own collection of found images to the pop art party, an “Atlas” of them in fact, stripped of consumerist self-deprecation; he turned the sentimentality of photojournalism into spare, grim history paintings; he abridged the march of expressionist abstraction towards its various logical conclusions—monochrome, machined hard-edge, or the histrionic erasure that made him rich. And he’s done a whole lot more besides. Richter’s originality, more than in any specific idea, is in his aggregation of disparate paradigms and in the sprezzatura of his plumb facture. By assuming the sober posture of a brilliant, if humourless German academic, he has covered it all in a thick glaze of genius.

It's when I saw the pencil drawings above that the pastiche notion hit me. My first thought was of wistful riffs on old-school German abstraction, but I can’t find a source. Willi Baumeister came to mind, and Hans Hartung, but they’re very different in spirit, more defiantly non-objective in keeping with a generation assailed by fascists. That’s not Richter’s tone. Growing up under communism makes creative types wily. If you imagine some of these drawings as negatives of schematic night scenes on a planet of many moons, they’re clearly landscapes. And some resemble prim imitations of Ben Nicholson’s reductivist planes tagged with mildew. In fact, these drawings are an encyclopaedia of pictorial references reduced to lines and smudges. I want another 20 years of Richter.

Back in communist Dresden, he was a star student of socialist realism. Unlike his Western cohort exhorted to produce new ideas, Richter was classically trained to seduce people into submitting to a freeze-dried ideology. Too clever for that, he slipped over to our side. Skilled, smart, hungry, and 29, the ‘mature student’ enrolled in an advanced Western art school where he sized things up fast. He found himself without technical opposition there, while still young enough not to drift into the nostalgia of the retardataire refugee. Instead, he deployed his enviable abilities to zhuzh-up the familiar styles of capitalist modern art while looking conceptual about it. The rest is art history.

Richter’s double portrait with Blinky Palermo from 1971 neatly resumes the world-historical situation of 20th century art. Portrayed as filled-in death masks cast in bronze, the communist-trained artist who can do anything faces the brilliant but unskilled child of liberalism. The eyes are closed, the mouths are shut. Richter was ten years older than Palermo who died abroad at 33, presumably of an overdose given his weaknesses. They met as students of prophet-like Joseph Beuys at the Düsseldorf Academy. If I had a lot of money, I would be an aggressive Palermo collector, elbowing-out the competition like a man possessed. A rusticator of high modernism, almost everything Palermo touched touches me. As for Richter, there aren’t a lot of people who can still dent that market. A child of liberalism myself, I’m in love with Richter’s mind, but I want Palermo’s objects.

About that mind, sure the products of a great artist will excite me, but I especially enjoy a shrewd strategist. Under the regime of originality, the territory you stake out early determines what you’re going to be doing in the studio long term. The art world is suspicious of weathervanes so the artists who impress me the most are original enough to get our attention, rigorous enough to earn our respect, but smart enough to plan for an emotionally sustainable career. Richter fixed it so that he can do anything he feels like within the range of his skills, since whatever he does will likely fit into his spongy corpus, even your grandfather’s moody old informel inkblots. Gerhard Richter is the artist of exquisite freedom.

mood, inkjet print, 2022.