Rashid Johnson’s subject is freedom; that’s what he says on the intro wall of Naomi Beckwith and Andrea Karnes’ survey of his career so far. Since none of us are free, nor is anything else for that matter, I wondered what he meant by the word. As far as I can tell, freedom is a hypothesis turned holy grail by the advent of democracy; or, more recently in America, since the abolition of slavery. Freedom is relative but never absolute: you can be freer, but you cannot be free. So, what does Johnson mean by “freedom”?

Humans are forever ‘not yet free:’ that’s life. But Americans—Johnson is one—are not yet free in more ways. The concept has weird dimensions in this society. For example, as we’ve seen in its politics, freedom is sacred even to those who don’t believe in it, or not as a universal principal, anyway: ‘How can I be free if you, who are so undeserving, are also free? What kind of freedom is that?’ A cross-talking patriotic mantra, the word is loaded down here.

In art, freedom means something else again. Johnson’s show demonstrates that he’s a freer man than most, certainly freer than conventional artists who only paint, only sculpt, only take photographs, only shoot videos, or only throw pots. Art is hard and most artists are lucky to master one medium. Johnson’s conceptualist ‘post-media’ approach liberates him to practice them all. He even creates opportunities for others to enjoy their creative freedom by providing performance spaces built into his show.

Extreme eclecticism isn’t the basis of his celebrity, however—he’s not among the pioneers of that particular liberty, and polymaths aren’t unusual in his cohort. He’s famous because he inhabits each of his distinct categories of art making more than plausibly. Redundantly meaningful, his corpus is as jarringly diverse as it is patently coherent.

Originality has cult status in his field, but it isn’t Johnson’s primary concern. Impressively, he is free of that too, and in his own peculiar way. You might even say that disinhibited imitation is a core freedom in this work, one that ultimately amounts to a meta-originality. Art is always ripe for emancipation from its shiboleths, and originality is one of them. Of course, Johnson has predecessors in this as well: the 80s appropriationists, ancestor worshippers who held the modernist canon up to an infinity mirror.

But that isn’t quite right in his case. Johnson’s appropriations are stealthy by comparison, and addressed more to the aficionado than to those who only have what the standard art-stingy curriculum doles out. Unlike the bald-faced copies of a Sherrie Levine or a Mike Bidlo, Johnson’s ‘altered quotations’ require you to be hip to the winks and wise to the footnotes. That might be what he means by the show’s title, quoting Amiri Baraka: A Poem for Deep Thinkers. His borrowings are informal next to the stiffer homage-ists who came before; Johnson has the subtlety and the smoothness of the second generation.

A better word for him would be ‘riff,’ in the jazz sense of a catchy motif on which this artist doesn’t skimp—hot-branded oak, houseplants in Bloomsbury-glazed pots, black-face hyper-doodles, graffiti-inflected abstractions, text on mirrors, auto-fiction, cosplay, carpets, shea butter, books, death... He riffs too in the literary sense of ‘variations on borrowed themes.’ Johnson extends his favourite ideas from the entire modernist canon—expressionism, neo-primitivism, the absurd, automatism, abstraction, reductivism, seriality, appropriation, graffiti—far enough to recycle them for the purposes of identitarian aesthetics, but not so far that an art lover would miss the allusions. That’s the ‘meta-originality’ I mean: a large cast of received ideas forms the basis of a self-reflective practice.

For me, the many ghosts and echoes of artists who came before—dead or alive—turn his survey into a teeming séance. A long parade of spirits crossed my mind as I negotiated the Guggenheim’s ramp: Duchamp, Guston, Pensato, Basquiat, Haacke, Beuys, Johns, Rauschenberg, Broodthaers, Burri, André, Kienholz, Beardon, Sherman, Jonas, Weems, LeWitt, Tiravanija, and at least three Grahams, Martha, Rodney, and Dan. A surfeit of referents, the psychic presence of a whole pantheon is particularly seductive to art buffs: we get to exercise our faculties when artists play charades.

Johnson is multitudes, the lawyer you send to argue before the Supreme Court for the century of jurisprudence at his command. I’m not sure why I’m late to the Rashid Johnson party. Access is the perenial problem with art, of course, something moving to New York has only partially resolved because so very much goes on elsewhere. Johnson’s name was familiar but didn’t evoke anything in particular, aside from books and banks of plants, so I was indifferent until I saw this show. I’m now embarrassed by my former oblivion because he was always good, and from the earliest works by the evidence of this survey. He isn’t so much an artist’s artist as a curator’s. I love work that knows things and knows that I know. Looking at it is like being smiled at.

As you would guess from the show’s quoting title, Johnson is especially generous to the literate. Among other things, his work amounts to a library of Black authors—resonant talismans of wit and ‘witness,’ massed and repeated in columns, as they would be in a university bookstore. They identify Johnson’s point of cultural departure as African American, and him as the child of a tenured historian in the specialty. As an artist-shaman of his cultural specificity, family advantage is evident throughout a scholarly corpus that is no less seductive for its erudition. But his frame of formal reference is broader than his cultural specificity, which it encompasses: he’s an insider stepping out with the purpose of looking back in.

One missing book kept coming to mind as I waded through the crowds, physical and metaphysical: Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities, a monument of social self-satire. For me, much of the show felt like a sidelong bow to Musil who reflected with irony on being a certain kind of Austrian. Johnson’s work establishes his deep grounding in the Afrocentricity that structured his youth, but it also feels like an escape from it, an elaborate, loving, respectful, brain-surgical exorcism. As a record of self-reflection, his work lets him have it both ways: like Musil, he is subjective and objective. Not only is that allowed—what isn’t in art?—it manifests a mystical self-possession.

Perfectly happy to be African American, Johnson is equally at home in the wider world where he gets to be himself with strangers. This is the poise his work presents to me. And he’s also happy being a prosperous bourgeois from the evidence of his ‘family life’ videos. Domesticity is a rich and fascinating theme in this work—I see it everywhere. To me, his recent “look how we live” videos are more candid than exhibitionist, and refreshing, given the undying cliché of penury in Johnson’s profession. There’s also an instructional subtext to them: exercise, brush your teeth, tend a garden, mentor your children, care for the elderly and, especially, read books. One includes a glimpse of the family’s choice art collection: the right Bob Thompson, the right Glenn Ligon, and an embarrassment of riches in fine African masks. Such is refinement’s equivalent of pulling up in a Lambo.

In their argument for Freestyle, the 2001 exhibition that they co-curated at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Thelma Golden and Glenn Ligon elaborated on the term “post-Black” which is helpful when thinking about Johnson’s work. At 24, he was the youngest artist in the groundbreaking show.

One piece made me laugh out loud, though the humour is dark. Four for the Talking Cure, 2009-12, is a set of zebra-pelted daybeds arranged in a planted square. It’s topped with an abstract Afrofuturist sculpture that I read as the rhombic antena of shortwave radios. This last feature—yet another repeated riff, like the presence of ham radios in other works—is a likely salute to his father whose field is electronics. I thought of the uber-simple furniture of Donald Judd or Scott Burton upholstered to make a new point: thanks to white supremacy, Black analysands all have the same psychological issues, so why not pool their therapy and beam it abroad?

Johnson’s rich humour is usually too bold for laughter, as if daring viewers to register amusement. His Ed Kienholz-channelling wall installations are a case in point. Tiled and/or mirrored constructions are smeared and/or splashed with a gum of black soap and black wax; their shelves are stocked with books on the Black experience and albums by Black musicians; there’s a potted plant here, a telling knick-knack there, and bowls of Beuysian shea butter. Living with one must be like having a portal into someone else’s home—indeed, seeing yourself in a patch of their wall—let’s call them ficitional Black characters. Imagining these works in a rich person’s house made me think of Chardin and Boucher’s fibbing pictures of ‘life among the lower orders’ with which the minor Bourbons surrounded themselves in their appartements at Versailles. I thought of Marie-Antoinette milking cows at Le Hameau, and of torn jeans on millionaires. Unlike Musil, Johnson’s rhombic satire is inclusive.

In these ‘theatre-set’ wall works, Johnson rubs shea butter on Michael Fried’s “theatricality,” moisturising sense into the dry minimalism that Fried indicted and that Johnson tags and, in some cases, vandalises. Like a lot of his work, it has the bones but not the features of reductivism, as if you were to put a deck, a shed and an outdoor shower on a Miesian villa.

A jewel of an early performance video, Me, Tavis Smiley, and Shea Butter, 2004, is shot from a fixed camera and not quite two minutes long. We spy a Black male (the artist) naked but for a towel, moisturising in the bathroom to the sound of talk radio. The program is The Tavis Smiley Show—the first NPR production with an African American host—that aired between 2002 and 2004.

Many thoughts went through my mind as I craned past a clutch of viewers to see the piece. Johnson was a firm 27 when he made it, so desire should have been one of those thoughts. But the performance is too perfunctory, and the video too short to be erotic for long. Caillebotte’s Man at his Bath of 1884 came quickly to mind. I also thought of the young Zhang Huan’s textile-free performances of the 1990s. And a memory from childhood surfaced, of my mother, likely also moisturising behind the closed bathroom door. Through it, one could hear talk radio in French. Most evenings, while the family watched television in English (her husband’s preference), earphones provided the aural privacy of her own linguistic space. Johnson enlists radio to point out that even interiority is culturally determined. Again and again, his work qualifies what is meant by freedom.

Inevitably, I thought of the female nudes and odalisques of the European tradition, from the Venus of Willendorf to Bonnard’s wife Marthe. How elegant of Johnson, I thought, to code-switch so smoothly between our Chinese-walled genders. And how daring to invite himself into the feminist canon of critical self-portraiture—Wilke, Schneemann, Mendieta, Benglis, Lassnig, et al. A towel—the etymological toilette of hygiene and art history—provides modesty as the artist rubs Africa’s golden nut butter onto his torso and limbs.

A substantial wall label mentions the “self-care” of the moisturising ritual and the Black broadcaster’s empowering voice. It notes precedents such as Bruce Nauman’s Art Make-Up, (1967-68), where the white conceptualist paints his face and torso a sequence of colours ending in black; and, by contrast, Pope.L’s self-explanatory I Get Paid to Rub Mayo on My Body, the Franklin Furnace performance of 1991. But the museum’s didactics are conspicuously silent on how Johnson deftly negotiates eros, or how he turns viewers into voyeurs.

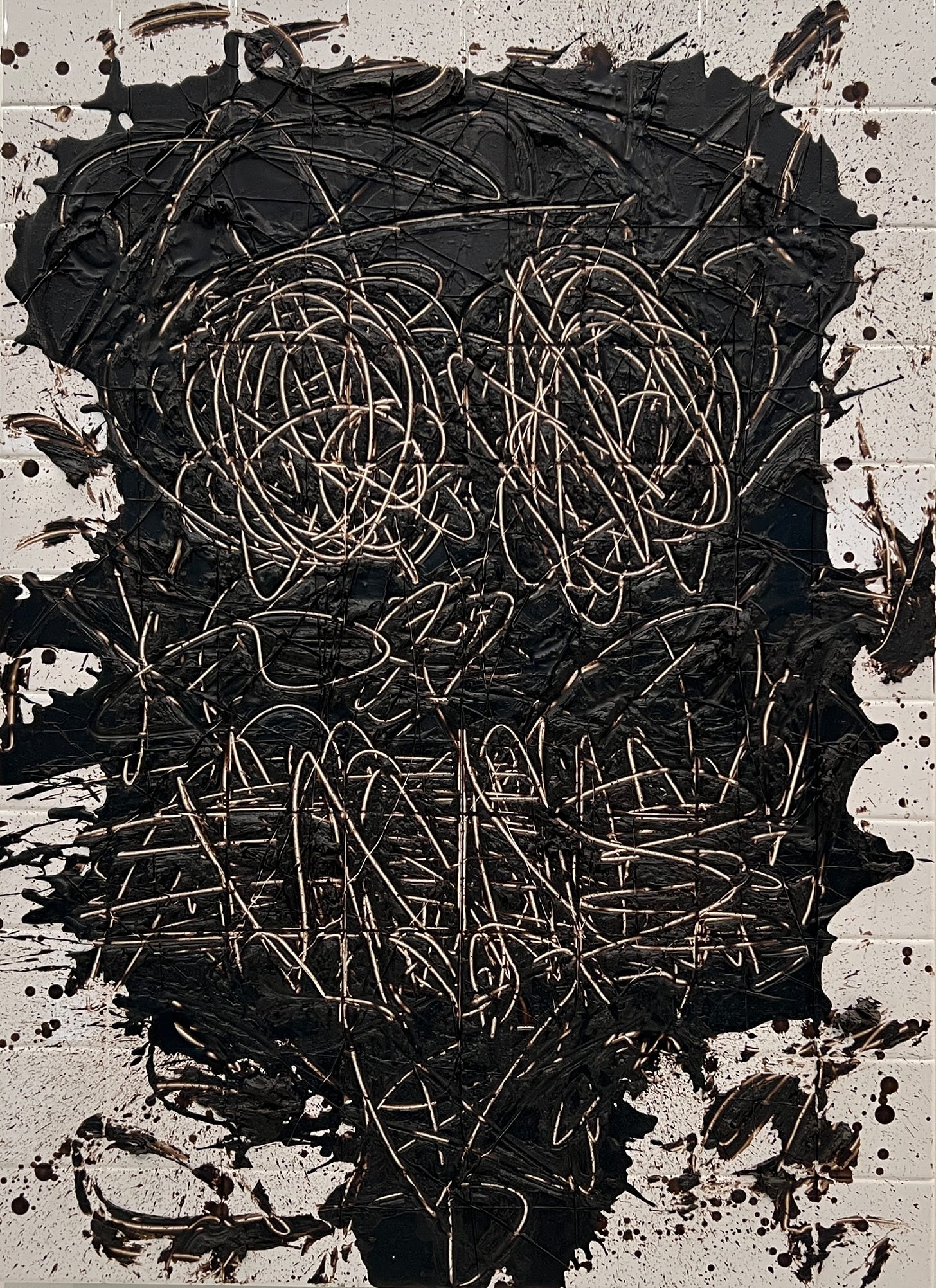

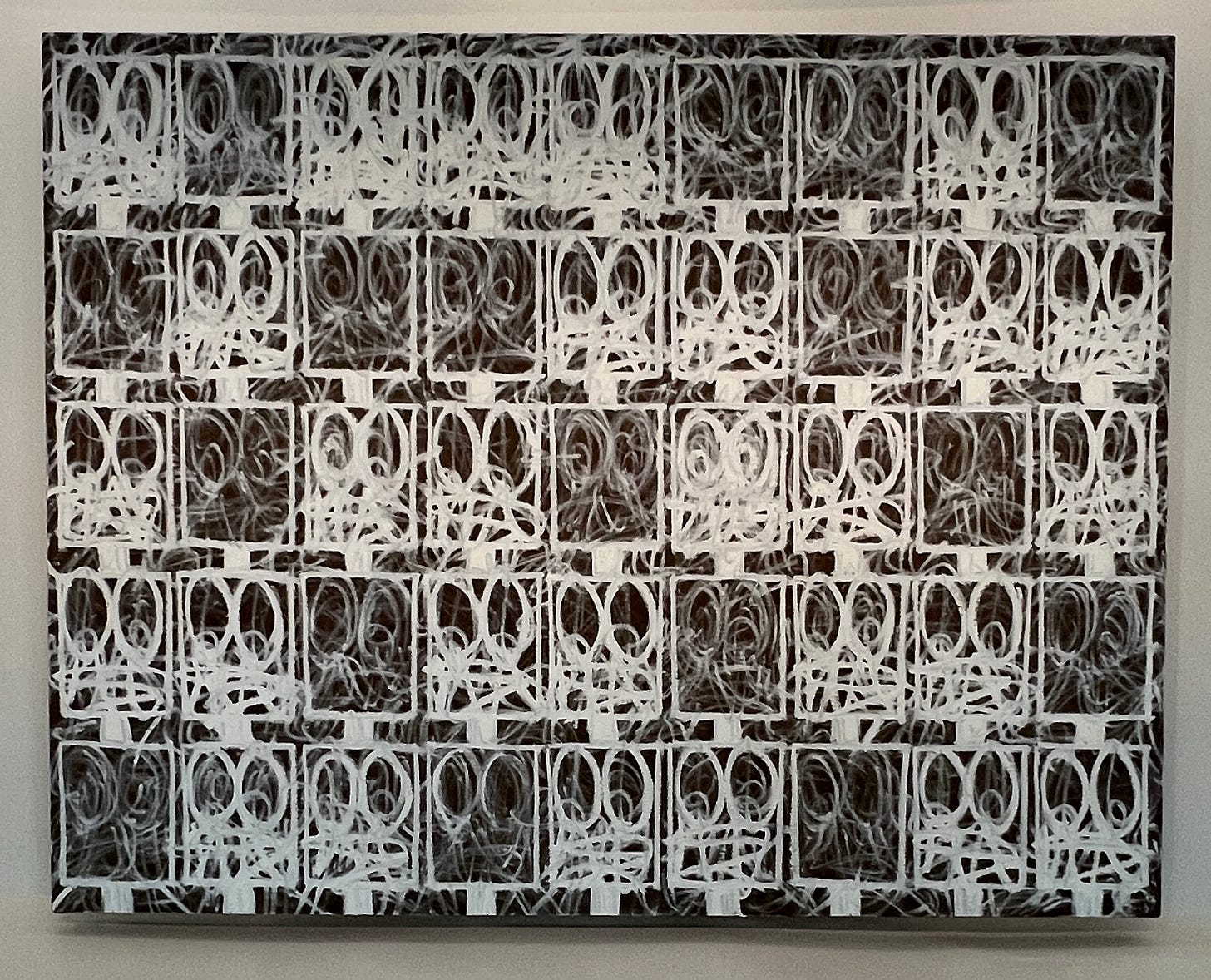

With his series “Anxious Men,” Johnson contributes a late addition to the canon of messy scribbled faces. Their white eyes and mouths are scratched into hot black wax. Imagine if Jean-Michel Basquiat had collaborated, not with Andy Warhol and his colourful silkscreens, but with Richard Serra and his black oil sticks. More recently, a calligraphic bunny-ear face is multiplied in Warholian repetition across broad grids. Riffing on the expressionist masks of 50s art brut and, more immediately, of the downtown 80s scene, Johnson deploys his like so many doodled signatures. He violates expanses of white tile with them, or decorates ‘domestic’ wall installations, or surprises you with the figural texture of a boxy monochrome planter.

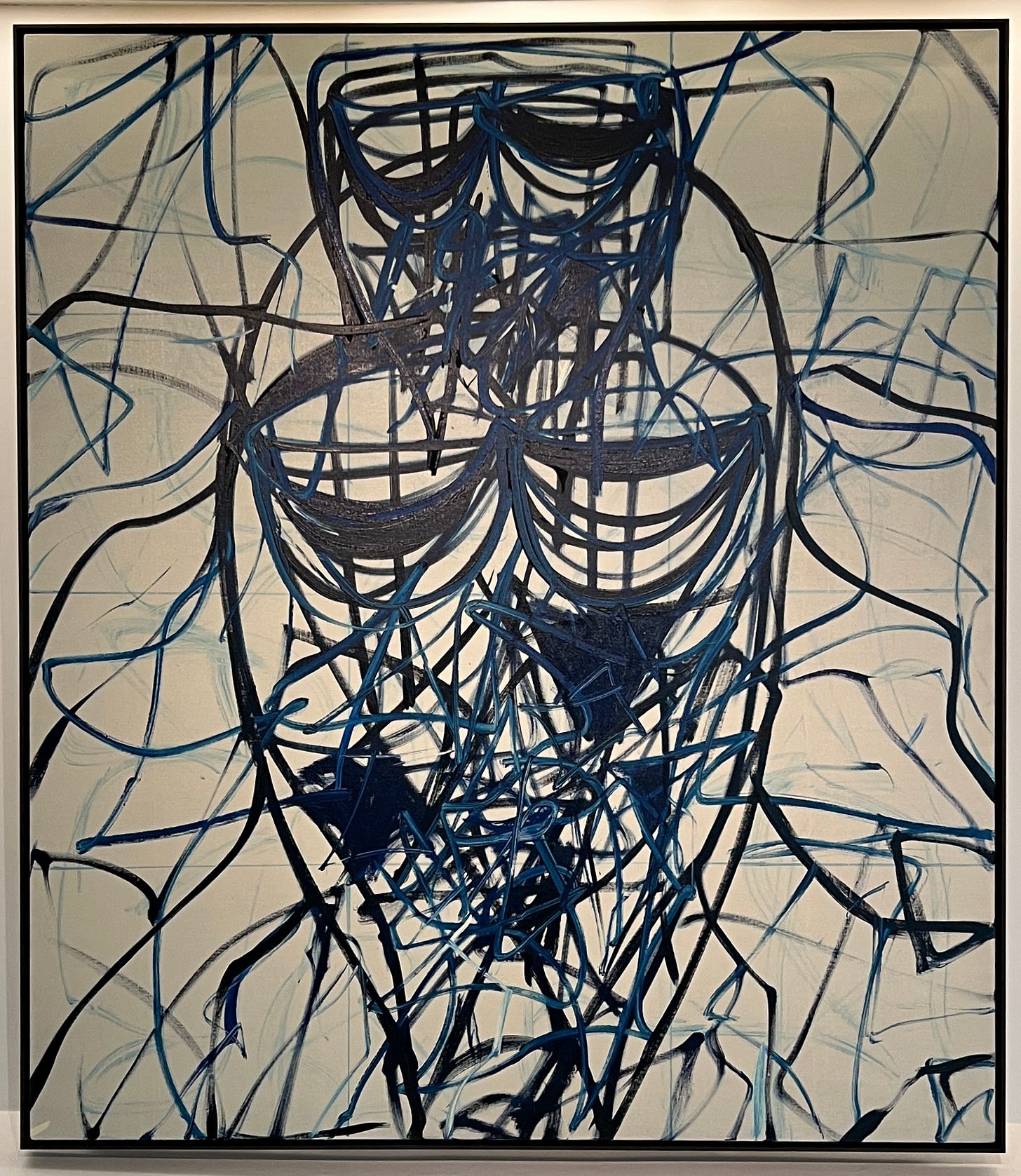

The “Soul Paintings” use graffiti as a springboard for abstraction, like surrealism was for Pollock and Rothko, or landscape for Kandinsky and Mondrian. He turns street tags into an abstract expressionism of jeering aggression, but in an ironically chiller tone compared to the provocative “Women” by Willem de Kooning that the pictures conjure for me.

Johnson’s echoing provocations are equally blunt and sly. If you look carefully at the “Soul Paintings,” past the lovely Brice Marden-isms in the margins—and don’t ignore the double-entendre—you might notice how Johnson reconciles the fractures of the younger de Kooning, the out-of-control exuberance of mid-life, and the sweet grace of the hero in cognitive decline. Somewhere in there is a deathless “soul” that Johnson rescues from the ether by reincarnating it as a mask.

Eventually, his populous tags morph serenely into the “God Pictures,” a reductive pattern of pointy mandorlas. Refered to as “vesica piscis” in the extended label, it’s the “fish blader” of sacred geometry. Formed by intersecting identical circles, the cypher is reminiscent of lips and boats when presented horizontally—as they are in some of his paintings and sculptures—or of spearheads and lanceolate leaves oriented vertically in the “God Pictures.” Johnson syncopates vegetal reds with white outlines, to complement green plants and flatter black skin. If his subject is freedom, his theme is transcendence.

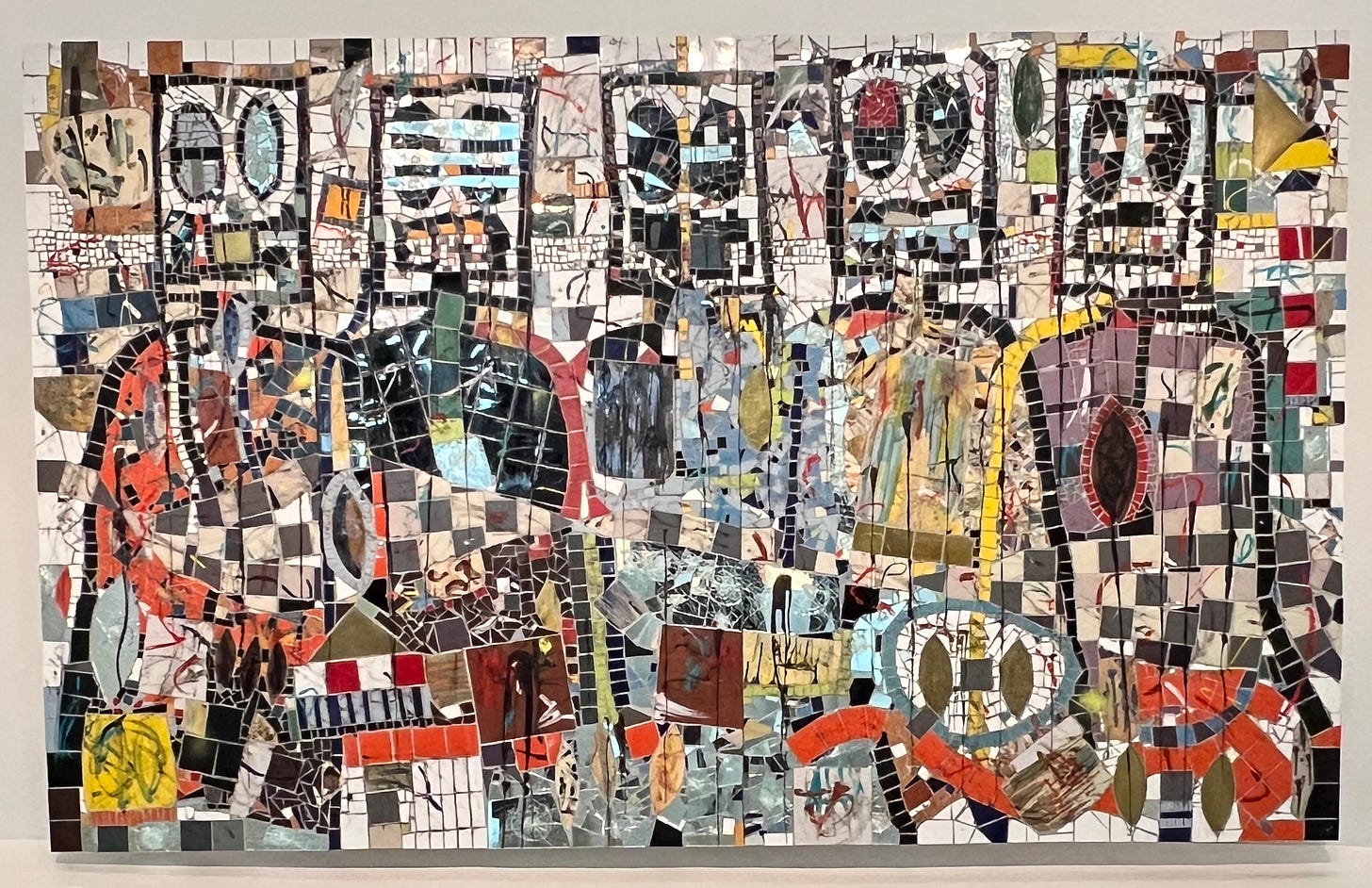

The punning “Broken Men” series of 2019 invests mosaic with clownishly expressionist angst, but without compromising the medium’s opulence. Here’s a tart example of reconciliation. Imagine an early Byzantine church devoting its glinting tesserae to intergenerational trauma rather than resurrection. Instead of prelates and saints, the congregation is watched over by a procession of mocked and damaged souls.

The downtown riffs kept moving uptown as I gravitated to the top of the ramp where external references start to thin out. Looked at through the traditional ‘education-through-imitation,’ one might say that at 48, Johnson has reached full maturity after a long apprenticeship of staggering brilliance. Despite the often grim historical allusions, his work’s good natured intelligence is relentlessly uplifting; by the end, my face ached from smiling.

Johnson’s recent houseplant installations are institutionally irresistible but challenging for viewers and museums alike. They are also libraries and collections of ceramic pots, on top of being two-for-one nods to Sol LeWitt and Dan Flavin. I had seen some before but was mostly just confounded. Their wit, coherence and generosity weren’t revealed to me until I saw this show.

An epic multi-part ‘plant’ installation completes the itinerary. Titled Sanguine and commissioned for the exhibition, plants “fly away” from it—instructed by those very words scrawled on a nearby mirror—into Wright’s yawning void. In one section, Johnson includes a crisply edited, big-screen video of his family life. I spotted a rolled carpet—a prop from The New Black Yoga video?—tucked between the parti-glazed planters that he throws himself. On another section, he hangs a big restful abstraction from the “God” series. All of these details, along with his trademark books and shea butter—and an upright piano hidden up behind the leaves—increase the domestic charge of the indoor monument. Conveniently for plants, Sanguine is installed just below the skylight that showers it, and the escapees, with nourishing daylight. Johnson turns the building into a conservatory for photosynthesising angels.

How are they watered? These ‘living’ installations ask a lot of an art museum, on top of the lofty price. They require the constant attention of a conservation department to keep them alive. Most museums are short of green-thumbed conservators, so would struggle to accommodate one of these works. Moreover, the insects that plants harbour pose a risk to the larger collection. Notice how the museums that own one—the Whitney Museum of American Art and the National Gallery of Canada are two—install them in public spaces, well away from vulnerable paintings and drawings. To the eyes of museum insiders, the prestige represented by these challenges deepen the prestige of having a big Rashid Johnson. That too is a hallmark of the artist’s conceptual framework: the implications are layered, some only available to a minority of initiates because mites aren’t visible to the naked eye.

There’s a commercial shrewdness to this practice, equal to its aesthetic sophistication. Johnson has managed his career beautifully so far by using installation as haute couture and painting as prêt-à-porter, with ceramics doing double-duty. Stan Douglas does something similar with photographs; they’re more broadly marketable than his big video productions that museums love for their surpassing intelligence and tiny editions. The institutional works anchor the artist’s reputation in the public sphere, which confers a lust-inducing (and price-increasing) glamour on his more conventional collectibles.

Johnson’s heterogenous sub-practices are distinct enough, one from the other, to keep the commentariat reaching for caffeine, and coherent enough as a corpus to preempt the charge of bricolage. He’s no dabbler, but a high-wire walker who may or may not fall to the ground. His career should be taught in art schools, alongside fellow aerealists Ugo Rondinone, Wael Shawky, Pierre Huygues, and Ai Weiwei. Like him, his international colleagues demonstrate that an artist need neither starve, nor suffer repetitive motion syndrome to inspire dissertations. And, like them, Johnson knows that each work has to stand on its own and not rely too heavily on the aggregate brilliance of the corpus. These aren’t sentimental souvenirs like signed baseballs, but the actual buttresses of an admirable career. Because of conceptualism, artistic leadership operates in a different register today, reminiscent of the Renaissance polymath.

In his interviews, Johnson exhorts viewers to think of themselves as “witnesses” when they move among works of art, as if in anticipation of making a police report. I would add that they should slow down and be quiet to assimilate his referential sonority. By choosing radical variety—in the interest of brevity, I skipped over his use of dance, music, and poetry—he has mapped out an active and stimulating life for himself, insulated from ennui. Like a good likeness, the show forms a convincing representation of artistic freedom. As I was leaving, I thought: “How liberating to be Rashid Johnson, and how exhausting.”

His unbound practice notwithstanding, freedom isn’t real because it’s always conditional, which defeats it. Like me, Johnson is constrained by his body, the requirements of air, water, food, shelter, sleep, and fellowship, the fact of gravity and the hegemony of time. Lots of people have agency over each of us, while everyone who ever lived is a subject of history, rather than of himself. We have been mired in untruth for countless centuries, language is a prison, virtue is a jail, and self-expression is for fools. Still, Johnson’s culture-expressing efforts remind us that we can see freedom’s light when we look at art.

What a terrific essay. I wanted to go straight to the Guggenheim...