for Ann

Because darkness is plural in Latin—tenebrae—it’s also plural in Latin languages: le tenebre, las tinieblas, les ténèbres. Multiplicity casts a poetical spell on darkness, making it dreadful and exciting for imaginations roused by it—'Things are stirring in the shadows. Should we turn on the light?’

We get the English word ‘tenebrous’ from tenebrae, though to English ears no noun can hold a candle to Anglo-Saxon ‘darkness.’ ‘Tenebrism’ is an art historical term that refers to the dominant movement in painting four hundred years ago. It was initiated by Caravaggio (1571-1610), the first and most famous tenebrist, whose style spread across Europe like a flu. It’s a good word for pictures of high drama and lifelikeness set against formless gloom. It’s a good word to know in any case because tenebrism is undying in painting, photography, film and much else.

Tenebrae and its kin refer to something more literary and evocative than simple lightlessness. For that, Latins use cognates of obscuritas. Obscurity made its way into Middle English via the Old French obscurité, but the original meaning went adrift in the Channel crossing. Obscure means ‘hard to understand,’ or ‘little known,’ or maybe even ‘hidden’ in English, well before it ever means absence of light, and only then mostly in poems. For absence of light, we still prefer ‘darkness,’ our old friend.

Latins, I should add, prefer their darkness feminine. Both tenebrae and obscuritas are feminine nouns in Romance languages. I like to pretend that a taste for gender parity inspired the French to coin le noir, a masculine singular term meaning ‘the dark,’ as in ‘être à tâtons dans le noir’ (groping in the dark). But Italian and Spanish don’t have this usage; they just mean black when they say il nero and el negro. When these words are used as adjectives, there are feminine declensions to qualify feminine nouns—la pittura nera, la pintura negra, la peinture noire.

Seventeenth-century tenebrists loved to paint with black. They used it for the background murk and deep shadows that give them away. Tenebrous backgrounds heighten the impact of figures posed against them, such as spiritual heroes coming into the light from doing battle in the faithless gloom.

To get a rich black pigment at low cost, animal bones were burnt, like the ancient Greeks who burnt bones for the sacrament of thysia. To be precise, Baroque backgrounds are dark chocolate rather than true black, because the minerals in calcinated bones—iron and manganese—oxidise on contact with air, light, and linseed oil. Compared to lamp black, an opaque pigment made from soot that turns blueish when blended with white, transparent bone black tends to brown.

I don’t know what burning bones smell like, but presume that the odour clung to the walls when artists had to burn their own. Caravaggio did not. The Baroque painter par excellence, Michelangelo Merisi is better known by the name of his birthplace. He caused vast amounts of bone to be burnt during the decades of his greatest influence. His followers, I Caravaggisti, were legion. One of them surpassed the master in terribilità, a quality that makes art chillingly sublime: Jusepe de Ribera.

Ribera’s big survey at the Petit Palais brims with terrifying pictures, all of them terribly good. Benefiting from the reattributions of scholar Gianni Papi, curators Annick Lemoine and Maïté Metz reconnect the artist’s prodigious early phase in Rome to the long Neapolitan years of his spectacular maturity. Here and there, inching through the show, I caught a whiff, not of burnt bones, but of genius.

Only the vagaries of history can explain why so bewitching a magician isn’t better known to art’s broad public. Ribera’s exceptional talent kept him wealthy for most of his life. But the vitality of younger competitors—Luca Giordano et al—and perhaps remnants of his youthful profligacy, left him financially diminished as his energy flagged. He was revered by 19th century French painters—Géricault, Delacroix, Courbet, Millet, and the hispanophile Edouard Manet whose life-size Dead Christ with Angels is latter-day tenebrism.

French poets loved Ribera too. Baudelaire, with his taste for beautiful ugliness, found a soul mate in the painter of withered flesh. Théophile Gautier is effusive in the superquotes— “It’s a fury of brushwork, a savagery of touch, a bloody intoxication that is barely imaginable.” That sounds more like Willem de Kooning, frankly, than meticulous Jusepe de Ribera. Gautier gets closer to the mark with “The truth, always the truth, that is your only motto.”

But there is more than mere truth going on in these pictures, there is cunning propaganda. Since early in the 1500s, Catholics had been engaged in a ruthless campaign against Protestant dissent. Not Christianity’s first civil wars, but they lasted for an ugly century. By the time Ribera was active in Italy, the Counter-Reformation, the war’s cultural offensive, was spending lots of money. As the Church reformed and rebranded itself, guided by the Council of Trent, it was a golden age of patronage for talented artists.

Ribera’s intuition about how pictures could best renew Catholicism attracted attention early on. The young Spaniard wasted no time in appealing to major Roman patrons—Farnese, Giustiniani, Borghese. The Spanish court back home heard about him too from its emissaries in Rome and ordered pictures.

Born in 1591 in Xàtiva, a Mediterranean town in the region of Valencia, Ribera spent his life in Italy after sailing to Rome at fifteen. Following a decade there, he moved to the Kingdom of Naples, then ruled by the Spanish crown. That’s where he painted his most fearsome martyrdoms and mythological scenes, as well as touching portraits of saints, sinners and marginals. He was the dominant artist of the Neapolitan court for decades. Ribera died at sixty-one in Naples of an unspecified cause.

For those of us who think of him as the heir, it's intriguing to imagine that the boy Ribera might have known Caravaggio in Rome. They likely overlapped for a few months before the father of tenebrism fled after killing a nobleman in a duel. We know that Ribera moved in Caravaggisti circles, at first as an art world jobber. That’s where he gained the sobriquet “Lo Spagnoletto,” the Little Spaniard.

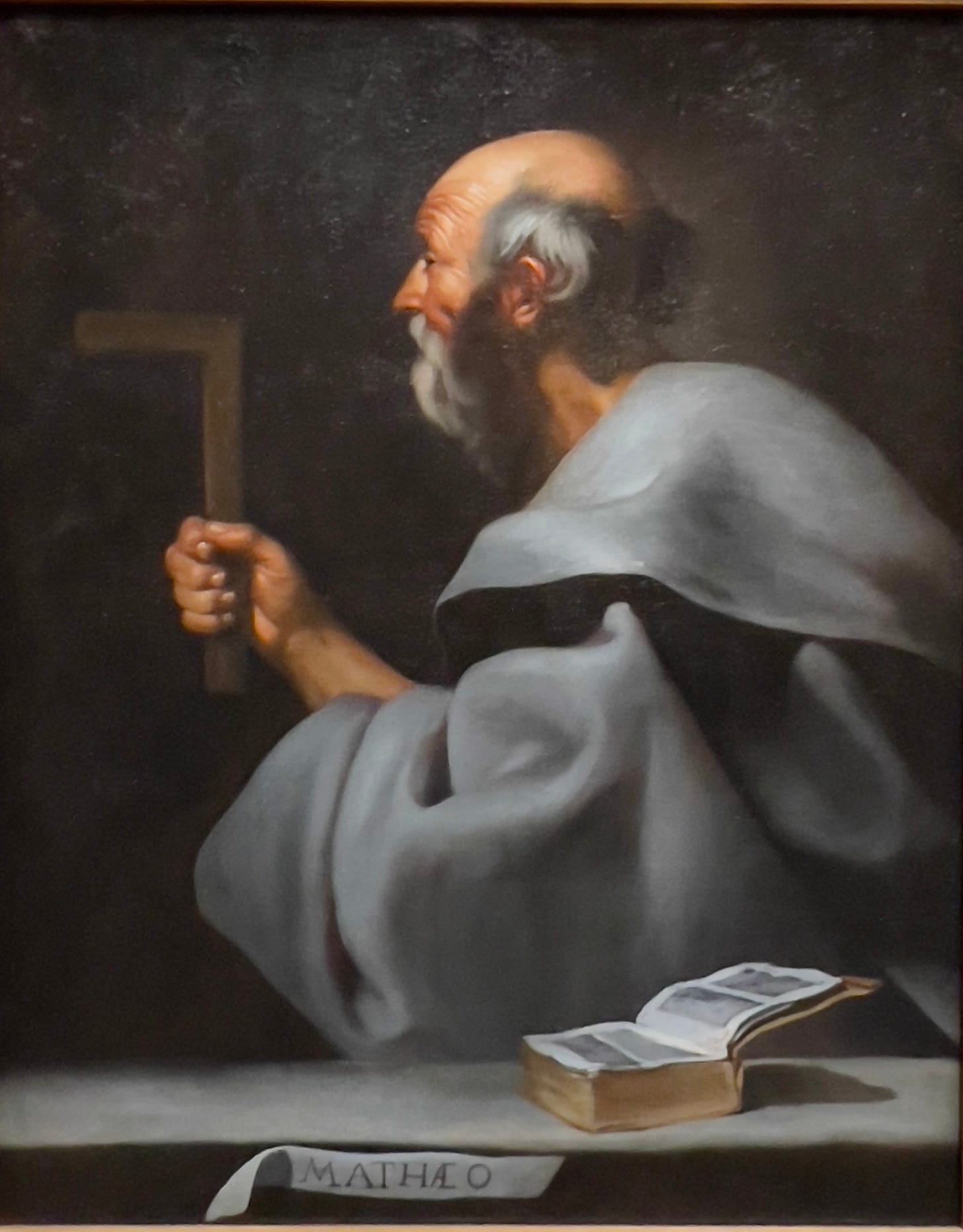

There was nothing little about his talent, though, which was soon revealed. Around 1607, when still in his teens, his Apostolados, or apostle portraits, began to appear. Two of the earliest depict what would become his signature subject: old men. I like the prodigy’s Saint Matthew, the former tax collector who became a biographer of Christ. The clever “Little Spaniard” has him holding a square to promote the rectitude of his gospel.

But it was his portrait of an older woman that bolted me to the floor, a picture that deepens and qualifies Ribera’s contribution to art history, and makes me think that he fails as a propagandist by soaring as a painter. Saint Mary of Egypt was painted in 1641. By now 50, Ribera was at the peak of his authority. The pathos of this life-size picture is so sublime that it takes you well beyond pity for the severe deprivation, and up into the thin air of awe. I felt a similar emotion at my first sight of a sadhu in India. A wizened man of perhaps 35, his hair bleached white from the sun, his skin parched a shade of bone black, he lay on the sidewalk in rags, smoking a cigarette, his eyes focused on nothing as he waited, indifferent, for death.

How is it possible to convince yourself that life is not worth the effort? To renounce the bliss of the senses for the abstraction of spiritual enlightenment? And why should enlightenment require suicidal abasement? It’s none of my business, and I won’t attempt to turn a light on it, nor on the mentality of the ascetic idols of old school Christians. But I so love how they were painted.

Saint Mary of Egypt (ca 344-421) had been a young prostitute in Alexandria, not out of necessity, her hagiographers assure us, but out of lust. Ribera shows her later in life, around the mid-point of her 47 years alone in the desert. Painted with gaunt naturalism, she’s perhaps too pale for a desert saint, but might look familiar to riders of the New York subway.

According to her legend, when Mary was 29 and a veteran harlot, she tagged along with a group of pilgrims sailing for Jerusalem. It seems that she ‘slept her way’ to the Holy Land. At the threshold of the pilgrims’ goal, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher,—built where Jesus is believed to have been crucified, entombed, and resurrected—a mysterious force prevented Mary from entering. It may only have been the blunt force of acquired shame, but she appealed for help to an icon of the Virgin at the door who, miraculously, advised her to change her ways. Repentant, Mary entered the church and was blessed. Thanking the Mother of God upon leaving, Mary was then instructed to cross the river Jordan and head to the Judean desert to make her home there. She did, battled demons for many years, and gradually became a hermit capable of miracles.

A sadhu of sorts, Mary of Egypt is venerated by Catholics, but most deeply by the Eastern Orthodox Church, especially during Lent, as a symbol of human transformation through repentance. Ribera shows her praying beside her meager attribute, a crust of bread. Next to it is the skull of death reflecting her emaciated face. Her nose is red from the sun; the skull’s is black from absence. The composition is Spartan: jagged outcroppings frame a bedraggled woman in middle-age, naked but for a rough blanket gathered carelessly about her. Ribera defies us to find eros in her poorly dissimulated nipple. Mary’s days of carnal seduction are behind her, long since traded for the allure of sanctity.

The reason I’m struck by this painting is not because of its verisimilitude, or its pathos, or its doctrinal fidelity, but for Ribera’s astonishing empathy. He knows this woman—she was clearly painted from life—and we know her too, now. She is so plausible, so specific. We notice her neglected hair—perhaps for being recently fashionable—her hands, wrinkled and crooked from scratching out a life in the sandy wastes, and her gaze of indifference to anything but God. She is lost to us and to our vain world.

Mary died, we are told, shortly after taking holy communion from Saint Zosimas of Palestine. The monk had discovered her by chance the year before while in the desert for Lent. At her request, he returned the following year to give her the sacrament a last time. It was also Zosimas who would later find her corpse. He buried it with the help of a miraculous lion, then went home to tell her story to the world. It was recorded by Saint Sophronius of Jerusalem.

Repentance is fundamental to Christian theology, so repentant saints are common in Ribera. But his specialty were the excrutiations of the early believers. In the first centuries of our era, the ancient Roman’s made a spectacle of tormenting Christians. But the Wars of Religion (1562 -1648)—when pictures of cruelty reached their apogee—were the greater catastrophe. By the 17th century, Papal Rome had shifted resources to an all-fronts campaign of mass seduction. Culture became a theater of war where Ribera held high rank. Catholic churchmen enlisted the finest artists to remake the iconography in defense of the creed. And, to shore up their claims of divine favour, the pictures they commissioned were of the horrifying punishments to which Catholic saints were impervious, their faith being an inviolable armour.

Ribera painted the apostle Bartholomew several times, the saint who was flayed alive for his evangelism. Unlike the mythological satyr Marsyas, who suffered the same ordeal and whom Ribera depicts screaming as divine Apollo tears into his flesh, serene Bartholomew is shown suffering more for the souls of his tormentors than from the skinning. He beseeches us to save them, rather than himself.

Pictures of the apostle Andrew—a missionary fisher and the brother of Saint Peter—were also popular with the artist’s patrons. Ribera has him either embracing the wooden X of his crucifixion, or in the picture from his youth in this show, praying beside the saltire cross. Notice, behind the saint, the looming diagonal shadows that the artist liked so much back then.

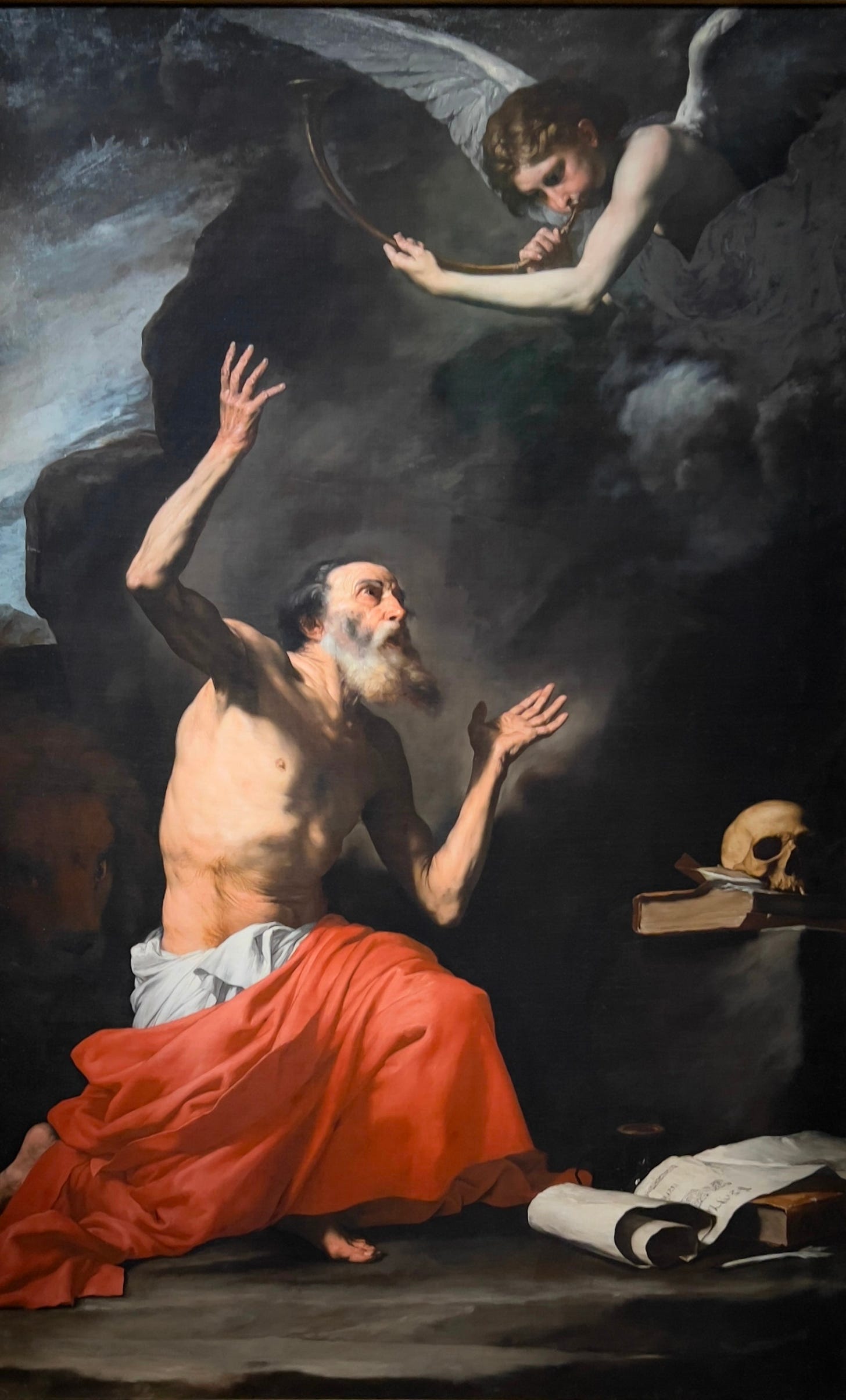

The biblical translator Saint Jerome, another desert penitent like Mary of Egypt, is jolted from his scholarly meditation by the trumpet of the Last Judgment. He wrote that its chilling sound frequently struck fear into him because of his old sins.

Ribera’s empathy moves me more than his thrilling skill. Therein lies my problem with him as a durable propagandist. His subjects and their life-likeness are overshadowed by the exquisite humanity of his observations. It’s so distracting. Despite their often grotesque depictions, I took pleasure—time and again—rather than repulsion, let alone moral instruction, from these grim works: the pleasure of his faultless eye and of its dizzying compassion. Ribera’s empathy was not for his legendary subjects, but for the flesh-and-blood people who posed for him, the poor men, women and children he immortalised with such accuracy and tenderness. He made miraculous icons out of burnt bones, ground rocks and the prosaic physiognomy of random mortals. Unimproved by him, they’re all the more poignant for it.

The stark ordinariness of Ribera’s figures enthralled his contemporaries by unsettling them. After the idealised Renaissance bodies and the languid limbs of Mannerism—Protestants condemned both, not without reason, as lascivious and idolatrous—it was time for homelier saints. Caravaggio officiated the marriage of melodrama and gritty realism. Ribera deepened the union by darkening the drama and exalting the unremarkable.

The rawness of Baroque painting clashes with the unchecked splendour of the architecture. Catholic churches became glittering temples that housed icons of cruelty and overcoming. I struggle to imagine the effect of these places on the peasants, soldiers, and labourers who first entered them. What was it like for the common folk to see such monumental luxury framing ghastly abjection? It taxes the mind.

Propaganda is a different beast today. The liars, scoundrels, and boors attempting to herd us electronically are shifting pathos from the elderly to the young. As they have for millennia, the young will task themselves again to build clear-eyed and just societies on the ruins of demagoguery. Look at the flattened cities, stolen lives, and soiled ideals. With so much of contemporary life backlit by glowing devices, obscurity may have been dispelled, but darkness has not.

Marc the eloquence of the writing… the depth of insight and empathy resound! Thanks for these words and becoming more familiar with Ribera is the prize for me.

Marc...this is one of your best pieces of writing ever. Congratulations. I will take you during lent to the service for St. Mary of Egypt..it is very moving. That he painted Mary in his later years is not surprising...it is in our old age that we understand her redemption and time in the desert as we begin our own.